Steve Dunham’s Trains of Thought

Return to the home page

“Commuter Crossroads”—More Topics

Commuter Crossroads main page

Commuting by bus

Commuting by bicycling and walking

Commuting by rapid transit and trolley

Commuting by train

Commuting by car

Diving Into a Vanpool

By Steve Dunham

This appeared in the Fredericksburg Free Lance–Star on July 18, 2010, and is reproduced with permission.

“It’s hard to say what a normal schedule is,” Rick Hood, owner of ABS Vans, told me. I had asked to ride in a vanpool from Spotsylvania to northern Virginia for one day, and ABS found me a seat in one going from Courthouse Road in Spotsylvania to the Pentagon and Crystal City in Arlington. I was alarmed when I discovered that the van left at 4:30 a.m., but it was only for one day, so I decided to go with it. I told my co-workers I would be working weird hours: roughly 6:30 until 2.

Even though it was almost the longest day of the year, I didn’t see a hint of dawn in the sky when I left the house. I was at the commuter lot early, starring in my own zombie movie as I climbed into the van. All the other passengers seemed used to it and quietly took their seats in the dark, some of them hunkering down for a nap.

We left Spotsylvania with about five people aboard and picked up two more at a commuter lot on Courthouse Road in Stafford, and then resumed participating in the rat race on I-95. I was surprised to see how much traffic there was both north and south at 5 a.m.

That changed when we got off the highway up north. The streets were pretty much deserted, and the driver took the passengers to their individual buildings in Crystal City and Pentagon City and dropped me off around 5:30 at the bus stop, where presently a bus would depart for Shirlington, a few miles away. I was at my desk before 6 and, aside from one of the help desk guys I saw in the elevator, I wouldn’t see anyone else for more than an hour and half. In the publications group where I work, those who drive tend to avoid the rush hours by working later, typically arriving in mid-morning.

After an hour or so at work, I got an e-mail from Virginia Railway Express alerting me that my usual train was running half an hour late.

The cost of riding in an ABS vanpool varies, depending on where you are going. The one I rode between Spotsylvania and Arlington costs $195 a month. A VRE monthly ticket between Fredericksburg and Arlington costs $268 a month. For me, either price would be offset by $120 a month the company provides in “Smart Benefits”—we get either that or free parking. Some people have been riding one of the 35 ABS vans for 15 years (Hood started the company in 1988). Like VRE, the vans benefit from government spending; besides the tax dollars spent on highways, Recovery Act money is funding conversion of some ABS vans to use propane.

At 2:20 p.m. it was time to leave work; a bus ride to Crystal City would take about 20 minutes, and my pickup was scheduled for 3. The afternoon traffic was too heavy for the van to stop at every building where the passengers worked, so after fetching me from the Metro bus stop, the driver parked as people walked from nearby buildings or came out of the Metro station.

Around 3:30 we were heading south again. Sometimes the traffic on 95 was crawling; at other times we were speeding along and sometimes following other vehicles uncomfortably close. Last year, I had switched from the company shuttle bus to Metro buses because the shuttle driver did too much honking and tailgating. I hadn’t thought I was in danger, but I didn’t want to be part of it. Some days I hate VRE, but I hate aggressive driving much more.

Hood says the company has never had a fatality, and he thinks that vanpools are the most time- and cost-effective method of getting people to work. Unlike VRE, the vans will run on minor federal holidays if there are private-sector passengers who must go to work, he said. Also, vanpool riders, like other users of public transportation, can take advantage of the Guaranteed Ride Home program up to four times a year if they have unscheduled overtime or an emergency.

Otherwise, the vanpoolers are limited to the schedule of the van. This would be a major inconvenience for me, even if I found one that let me work till 5:30 p.m., as I have to do on many days. I also take advantage of the varied VRE departure times when I go to the doctor or the dentist, for example. However, people with rigid work hours might find that a vanpool schedule works for them. You can try an ABS vanpool free for one day. Call 540-659-6323.

The next day after my vanpool adventure, I was back on VRE. My co-workers might claim that I was still a zombie, but at least I was still asleep at 4:30 a.m., and when I went outside, dawn was spreading across the sky.

More “Commuter Crossroads”

Return to the home page

Is Virginia Ready for High-Speed Rail?

By Steve Dunham

This appeared in the Fredericksburg Free Lance–Star on June 20, 2010, and is reproduced with permission.

High-speed rail may be coming to the southeast United States. Is Virginia ready?

The federal government has made a down payment on a national high-speed rail system. The cities around Hampton Roads are working to make sure that the southeast high-speed rail corridor includes a branch to that area. The commonwealth is looking at ways to fund more passenger rail service. But building a successful high-speed rail system requires more than a plan and the money to carry it out.

“The Asian and European systems were not built in a void; they were the next logical step to take after existing and conventional” higher-speed rail “routes became congested,” wrote Kevin McKinney in his “Window on the World” column in Passenger Train Journal earlier this year. “… a solid traffic base was there to begin with. Second, there was a dense feeder network already in place consisting of other intercity rail lines, commuter rail, light rail, subways and buses.” He noted that one of the leading high-speed rail projects—Tampa-Orlando in Florida—has little in the way of public transportation to get people to and from the planned stations on the high-speed line. California—the other state that got enough federal money to really move forward with an actual high-speed rail system—is different: it has an extensive statewide passenger train network already, plus rail rapid transit in all its major cities.

Northern Virginia is in a good position to integrate high-speed rail service into its transportation network. It has Metro rail and bus service throughout the suburbs close to Washington, where the existing high-speed service on Amtrak’s northeast corridor terminates at Union Station. The traffic base and feeder network are there.

Norfolk looks like it will be ready. It is building a light-rail system, and Virginia Beach may get on board and extend the line all the way to the oceanfront. These cities lack an existing intercity rail line, but they are served by connecting buses to the Amtrak trains at Newport News, across the water. The daytime Amtrak train between Newport News and Boston (it stops in Fredericksburg) has been one of Amtrak’s best-patronized trains since it was inaugurated in 1976. Typically it is an eight-car train, and it often is sold out. Furthermore, Norfolk is trying to get regular Amtrak service to its side of Hampton Roads. There likely is pent-up demand that will be demonstrated if a daily train from Norfolk starts running to Richmond, Washington, and New York.

Richmond is the big question mark. It is the hub for central Virginia, but in several respects it is not ready for high-speed rail. Its principal Amtrak station is on Staples Mill Road in Henrico County, about five miles from downtown. That station is adequate for the northside suburban market, but not for the whole metropolitan area, and especially not for bringing people to Richmond. The Main Street Station downtown has been magnificently restored, but it is lightly patronized, because only the Amtrak trains to and from Newport News stop there. All the other Amtrak trains either terminate at Staples Mill Road or bypass downtown Richmond on their way to and from Florida, Georgia and the Carolinas. Also, Main Street Station, even though it is near the capitol, the state offices, and Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, has no rail transit at all, even though it is well situated as a terminus for commuter rail service. Richmond is on the mainline, but it is not ready to integrate high-speed rail into its regional transportation system.

Fredericksburg is on the mainline too, and just as in the Civil War, it will get some action because it is halfway between Washington and Richmond. But its bus service is skimpy, the commuter rail service to the station runs weekday afternoons only, and the station itself is short on amenities—the closest toilet, for example, is two blocks away. These things deserve improvement even for the existing rail service.

And is high-speed rail really coming to Virginia anyway? Sometimes I wonder. This year Virginia got a $75 million grant to add 11 miles of third track between Powell’s Creek and Aquia Creek on the CSX line, ostensibly in preparation for eventual high-speed rail. The Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation said that the new trackage would be compatible with 90 mph running. But earlier this month in an online forum, Virginia Railway Express chief executive officer Dale Zehner said that we should not expect to see trains go faster on this segment when the work is done. The speed limit will remain the same, a maximum of 70.

Twice a day, VRE warns its riders that there may be a high-speed train approaching on the adjacent track at Quantico. Maybe someday. But looking down the track, I’m not sure that any high-speed trains will be arriving soon.

More “Commuter Crossroads”

Return to the home page

Good Transportation Requires Thoughtful Planning

By Steve Dunham

This appeared in the Fredericksburg Free Lance–Star on May 23, 2010, and is reproduced with permission.

Improving regional transportation requires good planning, according to several professionals who spoke at the Rail~Volution conference in Boston in October, which emphasized transit-oriented development—public transportation that is part of the community.

Such development cannot be mandated or pushed on communities, said one speaker, Eric Fang, a New York architect: the communities push back with anti-growth policies and actions. Instead, he said, it’s necessary to find the right opportunity for developing land around the station. This is a concern that Spotsylvania will face as it adds a Virginia Railway Express station near New Post. Planned new VRE stations in Cherry Hill and Haymarket (at opposite ends of Prince William County) will face similar questions. Local governments need to consider the effect on ridership and revenues, the cost to the transit agency, long-term value, traffic impacts and taxable real estate, said Fang. Maximum commuter parking and single-use office buildings, he said, don’t yield positive land value to offset development costs.

Susie Petheram, a senior planner with a consulting company in Salt Lake City, said that the land around the commuter rail station in Farmington, Utah, was mostly undeveloped when the station opened in 2008. The city established a transit-oriented development zone before the station was built, but the initial proposal for the 450-acre area was for a mall and big-box stores near the station.

Alan Jones, a London transportation consultant, came upon a similar situation while helping the city of Edmonton in Canada create a development plan. Edmonton’s vision of the future (in a painting in a city office) was a 14-lane highway. Their idea of a town center, he said, was a Home Depot with a parking lot. Sound familiar? The city has inefficient growth patterns, he said. One center of gravity is the West Edmonton mall outside of town, and the city’s development has been on the outskirts. Even the city’s transit system, with widely spaced stops and higher speeds, encourages sprawl, said Jones. A similar result can be seen with the Washington Metro’s blue line to Franconia-Springfield: the outermost stations are more than three miles apart, and they are surrounded mostly by highway-oriented development, with easy pedestrian access only for the stations’ closest neighbors.

Farmington wanted something different and came up with a new plan that defines streets, subdistricts and block size, as well as streetscapes and landscapes: what the developed area will look like. Then the city had to show the developers what can work and why it can work. Furthermore, said Petheram, transit-oriented development may not happen all at once or all from one developer.

The kind of development Farmington almost got near its commuter rail station—big-box stores and many acres of parking—is what Kim Delaney, Growth Management Coordinator for the Treasure Coast Regional Planning Council in Florida, calls the evil twin brother of transit-oriented development: transit-adjacent development, which she said is not pedestrian-friendly. It’s merely something built next to the station, not something integrated with the station in a community.

Fostering economic development around a rail station, said Fang, requires keeping the parking away from the station; otherwise local business doesn’t benefit. It’s necessary, he said, to focus on the small scale. Then rail passengers interact with the neighborhood.

Here in Virginia we’ll need to consider factors cited by Petheram: density, diversity, design and varying levels of permanence (building exteriors, buildings themselves and the street network, which she pointed out is the most permanent). To make transit-oriented development happen, she said, requires a flexible regulating plan defining the site design, diverse uses, types of streets, pedestrian pathways and links to the existing and planned road network.

Another thought: Spotsylvania would do well to design its VRE station so that it could be a destination. Although the current VRE service pattern wouldn’t let anyone travel to Spotsylvania for the day, the Amtrak service would, if platforms are on the mainline and not just in the industrial park. Then people could travel by train to reach jobs in Spotsylvania, and a conference center at the station, almost halfway between Washington and Richmond, could be an attractive destination and an important part of transit-oriented development.

More “Commuter Crossroads”

Return to the home page

Health, Housing and Transportation Policies Can Build Livable Communities

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on Jan. 31, 2010, and is reproduced with permission.

“Smart, integrated planning is the key” to building livable communities, said Derek Douglas of the White House Office of Urban Policy. He was addressing the Rail~Volution conference in Boston in October 2009—an annual event dedicated to building livable communities. The Obama administration, he said, wants to see transformative investments in transportation so that federal programs work toward the same goals. Agencies are willing to work together, he said, but the laws behind the policies can be hurdles, specifying conflicting approval methods and timelines, for example.

Federal policies and how they are implemented locally was a major theme at Rail~Volution 2009. But the administration is “committed to doing it differently,” said another speaker, John Porcari, the U.S. Deputy Secretary of Transportation—for example, changing rules and regulations that work against affordable housing, and looking at outcomes rather than inputs. He said there has been a “beat to fit” way of doing things: beat programs into shape until they fit local needs. The federal government, he said, needs to be more performance oriented and less prescriptive.

Other speakers mentioned the difficulties that local planners have with federal policies:

Local governments are not configured to work with integrated federal policy, noted Jonathan Rose, a consultant from New York state.

And the federal government also needs to have a lighter touch yet hold people accountable, commented Congressman Earl Blumenauer of Oregon, the founder of Rail~Volution.

Peter Rogoff, head of the Federal Transit Administration, acknowledged some difficulties with federal processes. The federal “decision process takes far too long” in funding projects, he said, and it is complicated and sometimes creates “perverse results.” Instead, he said, the federal government needs to make sure that funded transit projects encourage dense development. This reduces automobile dependence and encourages healthier lifestyles.

The environment we build is the second-greatest influence (after lifestyle) on health, said Ron Sims, Deputy Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. Dirty air, he pointed out, doesn’t stop at regional boundaries. The federal government, he said, “will insist on regional planning.” We must also integrate the policies of transportation, housing and health, he said—for example, identifying corridors for affordable housing development. Under the existing system, he said, it’s easy for proficient people to get federal grants, but it doesn’t necessarily benefit the people who need the most help.

George W. McCarthy, Director of Metropolitan Opportunity for the Ford Foundation, said that the foundation wants civil rights organizations to weigh in on how transportation dollars are spent. Urban highways, he pointed out, have been built in low-income neighborhoods where land is cheaper. But constructing mass transit sometimes pushes poor people out as real estate values rise. Developers, said McCarthy, now favor mass transit because the market has changed: many seniors and young people want to live in healthy downtowns. He wants every federal program to have requirements for location efficiency and community health.

Community health, in all its forms, was advocated by Eugene Benson of Alternatives for Community and Environment in Roxbury, a poor Boston neighborhood. He called for “transportation justice”: transportation that is reliable, affordable, safe for all, environmentally good, with stable funding and open, democratic planning.

This locally expressed desire is getting a warm reception in Washington. We have a shared mission, said Deputy Transportation Secretary Porcari, concluding, “Livable communities are the foundation.”

More “Commuter Crossroads”

Return to the home page

A New Future for High-Speed Rail

By Steve Dunham

This appeared in slightly different form in the Fredericksburg Free Lance–Star on April 26 and June 21, 2009, and is reproduced with permission.

“We’d be going berserk if 43,000 people a year” were being killed on American trains or airplanes, Gil Carmichael told the Virginians for High Speed Rail conference in Charlottesville on May 8. High-speed rail is an ethical transportation system, he said: it doesn’t kill, it doesn’t waste fuel and it doesn’t pollute too much. (Japan has never had a fatality on its 130 mph bullet trains, in service since the 1960s.)

Carmichael is a former head of the Federal Railroad Administration. Ten years ago he presented his case for “Interstate II” or the “Steel Interstate”—a 20,000-mile network of high-speed and upgraded rail lines knitting the country together. Trains would be electric, and some of the system is already in place, such as Amtrak’s 450-mile all-electric Northeast Corridor between Washington and Boston, on which Amtrak’s Acela Express (at least for a few miles) travels at 150 mph. Most of the corridor has top speeds over 100.

Now Carmichael thinks that the transportation renaissance is dawning. By working with railroads to construct additional tracks and upgrade others, we can move toward a new interstate transportation system. The $8 billion in federal money for high-speed rail will move some routes toward 110 mph service—a speed, he said, compatible with faster freight trains. Virginia, he said (to my surprise), is in “high gear” and “moving rapidly toward high-speed rail.”

Three weeks later, Amtrak President Joseph Boardman echoed that thought at a high-speed rail meeting sponsored by the Greater Richmond Chamber of Commerce. “Amtrak can run at” high speeds—he mentioned 200 mph—“if states are serious,” he said. “Virginia is serious.” He cautioned, though, that one of his jobs is to manage expectations. The country is taking the first steps toward creating more high-speed rail, but the “first step isn’t 110” miles per hour. Reliable 90 mph service between Washington and Richmond would be good, he said, a thought seconded by some business people who mentioned the difficulty and expense of traveling between Richmond and Washington by air or highway. CSX and other freight railroads are saying that 90, not 110, should be the top speed for express passenger trains sharing tracks with freight and commuter trains.

Right now, the top speed for trains between Washington and Richmond is 70, which is the cruising speed for Virginia Railway Express trains between most stations. To go 90 would be a nice improvement, but it’s only 11 mph faster than what we had 40 years ago, when the train service was more reliable too.

Boardman noted that European high-speed rail is very high speed, and that’s how the French TGV’s name translates: “the very high-speed train”—it goes 180 mph or better. But even the Northeast Corridor speeds of up to 150 (an average of about 80, counting station stops) are much better than driving and are even competitive with flying. Since Amtrak introduced the Acela Express in 2000, he said, Amtrak’s share of combined rail and air travel between New York and Washington has gone from one-third to two-thirds.

That kind of transportation seems a long way off in Virginia, because our rail service doesn’t have the frequency, the speed or the relative reliability of the Northeast Corridor. But Carmichael and Boardman think it will happen.

Fredericksburg is on one of the “designated high-speed rail corridors” that President Obama displayed on a map in January 2009. The city wasn’t labeled, nor were any of the others, but the dots representing Richmond and Washington are connected by a red line: it’s CSX, which passes through Fredericksburg.

This red line, the Southeast corridor, begins in Washington and runs south to Raleigh, NC, then branches to Columbia, SC; Savannah, GA; and Jacksonville, FL; in one direction and to Charlotte, NC; Atlanta; Birmingham, AL; and New Orleans in the other. The Southeast “high-speed rail corridor” was actually designated decades ago, and over the past 20 years, “the Federal Government has taken small steps to lay the groundwork for an expansion of” high-speed rail and intercity passenger rail “but has provided little funding for these efforts,” according to the Federal Railroad Administration’s newly published Vision for High-Speed Rail in America, and “little” is an overstatement. The document notes that “funding for the program in most years was about $5 million.” To me, that would be a lot of money. In transportation, $5 million a year for the whole country is chump change.

“For too long,” Vice President Biden said on March 13, “we haven’t made the investments we needed to make Amtrak as safe, as reliable, as secure as it can be. That ends now.”

What will take its place? Amtrak’s share of the stimulus package will pay for a new bridge in Connecticut, rehabilitating stored passenger cars, positive train control (a sophisticated dispatching system), and a few other projects.

Obama’s high-speed rail funding is something additional: $8 billion to start turning the designated corridors into something more than lines on a map. He also plans to budget $1 billion a year over the next five years. But $8 billion for the whole country is not going to give us 110-mph trains through Fredericksburg. It is still a small fraction of the annual federal highway budget. Perhaps coincidentally, it’s the same amount that the federal government gave the Federal Highway Administration in September 2008 as supplemental funding to the money that came in from federal gasoline taxes.

The $8 billion is, as Obama put it, a “down payment.” It will go to projects that states have been planning and are ready to move forward with to improve intercity passenger rail incrementally, with a view to ultimately high-speed service. North Carolina, Pennsylvania, New York and California, as well as a compact of Midwestern states, have been doing preliminary work toward high-speed intercity rail and are good bets as recipients for federal grants.

What about Virginia? Besides the designated Southeast corridor, Obama’s map showed a red line to the Hampton Roads area. The mayors of Norfolk, Virginia Beach, Suffolk and Newport News were quick to pounce on this and say that they wanted high-speed rail on both sides of Hampton Roads. Right now, Williamsburg and Newport News have two pairs of Amtrak trains a day, and Norfolk and Virginia Beach have no passenger trains at all. But they do have a huge share of Virginia’s population and job market, and they recognize that good passenger train service will be good for their local economy.

Virginia has done some planning for expanded rail passenger service to Newport News and studied the possibility of running passenger trains to Norfolk and Virginia Beach. It has planned for added track capacity and, eventually, 110-mph trains between Washington and Richmond. It has already funded a few projects toward this goal.

One thing we can do in Virginia is go after some of the federal high-speed rail money (the U.S. government will be taking grant applications in the coming months) and use some of the other federal highway money coming our way to fund rail projects. Virginia isn’t obligated to spend all that money on highways. Pursuing high-speed rail service here in earnest would be good for the state’s economy and make it more attractive to business.

As promised, Obama has included $1 billion for high-speed rail in his proposed fiscal year 2010 budget. But following the precedence of decades, he proposed $41 billion for highways. If we keep funding highways vs. rail 40 to 1, we won’t get a national high-speed rail system soon.

More “Commuter Crossroads”

Return to the home page

Commuting Predictions for 2009

By Steve Dunham

This appeared in the Fredericksburg Free Lance–Star on January 4, 2009, and is reproduced with permission.

Getting to work is no fun these days, whether you’re commuting one mile or 100, and things are going to be a lot less fun in 2009. Sorry, but the truth hurts. Here are my commuting predictions for 2009, all of which are guaranteed to come true.

At the top of the commuting news for 2009 is Virginia Railway Express pursuing the luxury market. In an effort to rake in some dough, VRE is trying to fill its seats with higher-paying customers. If lots of people pay $25 to ride VRE to the inauguration and arrive in Washington in time to see the sun rise, you can bet that VRE will increasingly try to carry well-heeled tourists instead of commuters. VRE’s Sunrise Special and Sunset Special already run year round and are very popular. I don’t see why a lot of people wouldn’t pay big bucks to ride to and from Washington in the dark.

Our good friend Fred the bus will be tempted to go the same route (luxury service, not the route to Washington). Fred will declare that its buses, too, are “trolleys,” and charge people top dollar to ride around town. By the end of the year, Fred will also be offering horse-drawn tours, with Clydesdales pulling Fred buses through the streets.

Amtrak too is planning a new feature to attract more passengers. With gasoline prices temporarily down, it suddenly has some seats to fill and needs to lure some more people on board. The trains to and from Newport News will be rebranded the Mystery Train. Passengers waiting at Fredericksburg will have to search for clues about when the train will arrive and solve puzzles such as “Do I have time to walk two blocks to use a bathroom?”

While public transportation goes upscale to get more money from those who have it, the Virginia Department of Transportation is concentrating on commonsense, economical solutions to the road mess. First of all, it has found a cheap, workable solution to the gridlock at the Falmouth intersection: odd-and-even traffic days. Route 1 will be open on odd-numbered days, and route 17 will be open on even-numbered days. There will be no stopping for traffic lights. Everything will move smoothly.

Even more elegant and simple is VDoT’s solution to the congestion on route 3. Right now, everything is designed so that to get from one business to another, you have to leave a parking lot, drive on route 3, and enter another parking lot, even if the second business is next door. The obvious solution is to make additional lanes out of the parking lots. This will exponentially increase the movement of traffic, which is a good thing, right?

I have not forgotten about those of you who commute by bicycle or walking. The Commonwealth of Virginia is concerned that walking and bicycling in the Fredericksburg area are basically unsafe. It will pass a law making both illegal. It will enforce this just as strictly as the laws that govern speeding and yielding to pedestrians.

Finally, a prediction about Ground Hog Day. If the ground hog sees his shadow, we will have 52 more weeks of a transportation mess. Same thing if he doesn’t.

[More “Commuter Crossroads”]

[Return to the home page]

Bullet Trains Are Coming to America

By Steve Dunham

This appeared in the Fredericksburg Free Lance–Star on December 7, 2008.

“The adjacent track may have a high-speed train approaching.” Virginia Railway Express riders hear this announcement each time they arrive in Quantico.

Dick Beadles laughed when he saw a similarly worded sign outside the Quantico station. Beadles used to be president of the Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac Railroad (now part of CSX) and in his retirement founded Virginians for High Speed Rail. He knows that trains passing through Quantico can do 55 mph and that in the rest of the world, “high-speed rail” generally means 125 mph or faster.

We do have some high-speed rail in the United States. In Rhode Island and Massachusetts, there are about 18 miles of railroad line on which Amtrak’s Acela Express can travel at 150 mph, and for much of the remaining trip between Washington and Boston it can travel at 125 or 135 mph. And that’s it for world-class high-speed rail in the USA.

But that’s about to change. On November 4, Californians voted to build the first bullet train line in America. (Although the Acela Express would qualify as a bullet train, the railroad it uses—upgraded from lines built in the 1800s—would not.) The California High-Speed Rail Authority plans a new “800-mile network of trains operating up to 220 miles an hour and linking California’s major cities between San Diego in the south and San Francisco and Sacramento in the north.” The first line would connect Los Angeles and San Francisco, about 400 miles apart. The state expects to secure matching federal, local and private funding to complement the bond issue approved by voters. Once the system is built, it is forecast to operate at a profit. It also is expected to produce economic benefits 50% greater than its cost, in the form of 450,000 jobs plus new development, as well as significant reductions in pollution as travelers switch to the new electric transportation. California also expects that by building the high-speed rail system it will avoid spending an equivalent amount on additional highways. This is not all speculation: Californians see what has been achieved in Europe and Asia (China too is building high-speed rail).

California has taken first place in bringing high-speed rail to the rest of the United States, outside the Northeast. Virginia and other Southeastern states intend to improve existing railroads to create a passenger train system with a top speed of 110 mph between Washington and Atlanta, but progress, especially in Virginia, has been slow. North Carolina has done more, upgrading the tracks between Charlotte and Raleigh. But my guess is that we won’t see these higher-speed passenger trains until people demand a transportation network and an economy built on something superior to highway and auto industry dominance. Then we might start to catch up to South America.

Yes, Argentina looks set to beat California in building the first new bullet train line in the Western Hemisphere. This year, the country let contracts for a 440-mile European-style railroad between Buenos Aires and Cordoba, with trains operating up to 200 mph.

We’ve had more than 50 years of massive federal subsidies for new Interstate highways, and, at least in Virginia, we’ve produced a faltering economy of sprawl. But the age of the highway is ending. High-speed rail in Virginia won’t reverse 50 years of automobile overdependence, but it will be a step toward a different, better economy. That’s what the business men and women who formed Virginians for High Speed Rail believe.

In high-speed ground transportation, we’re decades behind Japan and Europe. We can let China and Argentina surge past us too, or we can get on board.

[More “Commuter Crossroads”]

[Return to the home page]

Nobody Likes Lafayette Boulevard

By Steve Dunham, copyright 2008

This appeared in different form as two columns in the Fredericksburg Free Lance–Star on July 20 and Oct. 12, 2008.

If you were king or queen, how would you begin now to improve Lafayette Boulevard? That’s one of the questions asked by the Fredericksburg Area Metropolitan Planning Organization and the George Washington Regional Commission.

On June 26, those organizations held a public workshop to kick off the Lafayette Boulevard Corridor Study, and the workshop was one of the best experiences I’ve ever had with government. The people from the commission, the planning organization, and consultant Kimley-Horn Associates were knowledgeable and welcoming. They asked for and received plenty of comments on traffic, pedestrian safety, bicycling, public transportation, and the Lafayette Boulevard environment.

If you’ve walked in the drainage ditches of Lafayette Boulevard, walked around the motor vehicles parked on the sidewalk, bicycled on Lafayette Boulevard, or even just driven the speed limit there, chances are good you’ve felt alone and even received a measure of hostility from shouting, cursing drivers. Traffic is out of control, generally merciless toward pedestrians, with speeding and tailgating common.

I left the workshop thinking, “Somebody is listening! Somebody cares!”

Not only are they listening, they are ready to crown me king. At least that was my understanding. If I were king, I would add sidewalks with lighting the length of Lafayette Boulevard, build a pedestrian and bicycle bridge over the Blue and Gray Parkway, run the Fred bus line every half hour all day every day and ticket all aggressive drivers.

What if you had $100 to spend on improvements to Lafayette Boulevard? That’s another question asked at the workshop. Would you widen the street? Repair the infrastructure? Build and repair sidewalks? The survey offered five more questions plus “other.” I would offer a bounty for the permanent removal of motor vehicles from the sidewalk.

The survey had three more pages of questions plus room for additional comments.

The results showed that nobody is happy with Lafayette Boulevard. The people surveyed indicated that it’s a difficult place to drive, and over most of its length it’s a terrible place to walk or bicycle. Hardly anybody is satisfied with its looks, either.

Drivers complained about traffic backups, especially at Harrison Road and the Blue & Gray Parkway during rush hours. The biggest complaint was having to wait through two cycles of a traffic light to get through an intersection. Heavy traffic volume was the second-biggest complaint, and many drivers mentioned difficulty turning out of side streets, as well as problems with blind corners. More travel and turning lanes were the most common suggestion.

Do Lafayette Boulevard users take advantage of public transportation? Of those who answered the question, almost a third said yes—mainly riding Virginia Railway Express or Fred buses. Those who don’t use public transportation cited slow travel time, limited hours of service, infrequent service, and public transportation not going where they want to go, among other reasons. VRE is pretty fast, and beginning in October 2008 the Lafayette Boulevard Fred bus started running hourly (instead of every two hours) on weekdays from 7:30 a.m. to 7:30 p.m., but neither service runs on weekends, and there are lots of places you can’t get to on VRE or Fred. At least the more frequent Fred service is a step in the right direction. A lot of people asked for shelters, benches, lighting, and better signs. Fred particularly has a lot of room for improvement in these areas.

If Lafayette Boulevard is less than ideal for driving or taking public transportation, it’s dismal for pedestrians and bicyclists. Not one person surveyed rated the road excellent, good or even acceptable for walking. Lots of people want to see sidewalks, crosswalks and a paved path—scarcely any of which exist beyond Sunken Road. The only sidewalks I’ve seen on Lafayette Boulevard outside downtown are short stretches by the Bennett Funeral Home and CVS. A big thank you to those businesses for taking a step in the right direction. Someday we should have sidewalks linking to theirs all along the boulevard. People also asked for pedestrian signals at intersections too, and you won’t find those anywhere on Lafayette Boulevard, even at the heavy pedestrian crossings by the train station.

No one rated the boulevard acceptable for bicycling either, and 16 people rated it downright dangerous. Only five people said they bicycle there, and only downtown. A paved path or bike lane was the most commonly suggested solution.

An overwhelming majority (92%) of the people answering the question said they would walk or bicycle more often if Lafayette Boulevard were improved to accommodate them.

How else should the road change? Only seven people rated its current appearance acceptable. No one thought it was good. Everyone else rated it poor or very poor. Besides improvements to the road itself (including places to walk and bicycle), people especially recommended lighting, landscaping, and small- and medium-size streetfront buildings, with a grocery being the number-one choice for another business.

Informed by the survey results, the corridor study will address existing transportation conditions, future travel demand, and accommodation of walking, bicycling, and transit in addition to driving, along with the connection between land use and transportation. Its purposes are to strengthen the community, coordinate land use and transportation decision making, accommodate increases in travel, enhance safety, improve aesthetics, coordinate with other plans and studies of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania, and come up with recommendations.

It will not address the engineering design of Lafayette Boulevard or intersections, site layout of private properties, or zoning.

The boulevard has potential. It intersects with the planned Hazel Run Trail, touches Lee Drive, passes the Battlefield Visitor Center, and almost reaches the Rappahannock River. Lafayette Boulevard could be a transportation artery that is easy to use without a car and welcomes visitors who arrive by train. It could be part of a network that makes it easy to get around the Fredericksburg area without driving.

Plans for improvement of will be presented Thursday, March 19, 2009, at Spotswood Baptist Church, 4009 Lafayette Boulevard, from 6:45 p.m. till 8.

[More “Commuter Crossroads”]

[Return to the home page]

From Metrocheks to SmartBenefits Can Be a Rough Trip

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in slightly different form in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on March 30, 2008, and is reproduced with permission.

The Washington Metro is pushing employers to provide transit benefits for their workers via paperless SmartBenefits rather than Metrocheks, which are essentially paper Metro farecards. If your employer helps pay your cost of using public transportation (typically in lieu of free parking), chances are you’ve been asked to switch to SmartBenefits.

If Metro is the only public transportation you ride, the new system is easy to use. You have to have a SmarTrip card, which comes with a personal account. Each month your transit money is transferred into your account, and the value shows up when you use the card at a Metro turnstile, farebox, or farecard machine. Most other bus systems in the Washington, DC, area accept payment via SmarTrip cards too.

For Virginia Railway Express riders, the shift to SmartBenefits is not so easy. You can’t use a SmarTrip card to ride VRE, or even to buy VRE tickets. Metrocheks can be exchanged for VRE tickets at many locations, but SmartBenefits can get you VRE tickets only through the Arlington Commuter Stores and their associated Commuter Direct mail order program.

I already had a SmarTrip card. It’s the only way to pay for parking at Metro garages, and it’s convenient for riding Metro. Add some value at a farecard machine now and then, touch your card to a turnstile or bus farebox and you’re on your way.

Now I needed to have my monthly benefits assigned to a Commuter Store account, not my SmarTrip card (the alternative is to set up a standing monthly mail order for VRE tickets). So I went to a different link that my employer provided; it took me to a vanpool page, and I had to choose VRE for the “vanpool.”)

I filled in the electronic form. Back came an error message: “Registeration Stoped … Last Name22407 you entered does not match the registration information for your SmarTrip account in the WMATA [Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority] database.”

Had I typed my name wrong? I filled out the form again and got the same message. I called 888-SMARTRIP and got a busy signal over and over.

Fortunately our company transit benefits administrator had some kind of inside channel and discovered that my name was spelled wrong in the WMATA database. Not surprising, considering the spelling in the error message and, for that matter, “SmartBenefits,” “SmarTrip” and “Metrocheks.” Without her help, I might have despaired of continuing my transit benefits.

Finally I got through to 888-SMARTRIP and a helpful person said she was correcting the database right then. I waited a few minutes, went back to the SmartBenefits website and got the same error message. I decided to give it 24 hours to take effect. This time it worked.

I went to the Crystal City Commuter Store (the other locations are Ballston, Rosslyn and Shirlington), and with trepidation handed over my SmarTrip card. Would they please verify that the money was in my account before I purchased my monthly VRE ticket? Yes, it was there, and since then I’ve bought my VRE ticket each month with no problem.

I’m glad that mail order is not my only option. When I worked in Alexandria, it once took four weeks for my paycheck to arrive by mail. I would not care to have my monthly VRE ticket arrive four weeks late. Eventually VRE intends to convert its ticket machines to accept SmarTrip cards. Until then, SmartBenefits is an awkward system for VRE riders, especially if you don’t work in Arlington.

And, like me, you may find it difficult to sign up using the SmartBenefits website. If you find your registeration stoped, I hope your company has a transit benefits administrator as helpful as mine.

[More “Commuter Crossroads”]

[Return to the home page]

Too Much Information

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on March 2, 2008, and is reproduced with permission.

The guy on the company bus was talking out loud to, apparently, his ex-girlfriend. The rest of us didn’t want to hear his half of the personal phone conversation, but there was no escape. After he got off, another co-worker turned to me and said, “There’s such a thing as having too much information.”

Indeed. I’ve been amazed (and a little alarmed) by the things some people say out loud in a crowd. One man sitting behind me on the train asked, “Did you think about me last night?” I hope he wasn’t talking to me! Some conversations demand a little privacy or discretion but instead become a public display. As P. J. O’Rourke wrote in The CEO of the Sofa, some cell phones “come with an earpiece and a microphone built into the wire so that cell phone users don’t even look like they’re using a cell phone; they look like crazy people raving on street corners.”

I was surprised by one man who walked down the train platform asking, “Do I add value?” I almost laughed out loud until I realized he was talking on a hands-free phone and possibly repeating a question from an employer who had questioned his worth. I would want to have a conversation like that face to face, with the door shut.

Last month two men on the train started discussing, out loud, a problem at one of the national laboratories, a contract that was being opened up to competition and whether and why “Jay” was going to investigate the program. Loose lips can sink ships, but I imagine they can sink companies and contracts too. Only the day before at work, we had gotten a security briefing that warned us against discussing confidential business in public places, because even isolated pieces of information can add up to a security problem. A dozen people, a lot of them government employees or government contractors, could have overheard that conversation on the train, and I’ll bet I wasn’t the only one who knew which national laboratory the two men were talking about.

On another day, one passenger informed all of us what plane he was catching, where and when, what places he would be going, and when he would be back. He was talking on the phone, but loudly enough for those around him to hear. For personal security, I wouldn’t want to announce to a group of strangers what days I would be away from home. If, furthermore, I were taking sensitive business or government information on a trip, I would not want to give strangers my itinerary.

When taking public transportation, we can mentally and emotionally isolate ourselves from the people around us. But that doesn’t give us privacy. We are more like ostriches with our heads in the sand, and although we might achieve a feeling of being alone in a crowd, the illusion ends when somebody starts talking out loud on a phone. “Hi, I’m on the train” just sounds like needless information, maybe even to the person on the receiving end of the phone call. Conflicts in personal relationships, contractual questions, problems at work and travel plans are possibly more information than you want to make public and more than others want to know. Somebody who does want to know might be up to no good.

There’s such a thing as having too much information.

[More “Commuter Crossroads”]

[Return to the home page]

Transportation for Tomorrow

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in slightly different form in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on Feb. 3, 2008, and is reproduced with permission.

“The U.S. now has incredible economic potential and significant transportation needs,” according to Transportation for Tomorrow, a report issued in December by the National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Study Commission. “We need to invest at least $225 billion annually from all sources for the next 50 years to upgrade our existing system to a state of good repair and create a more advanced surface transportation system to sustain and ensure strong economic growth for our families. We are spending less than 40% of this amount today.”

The commission, established by Congress with bipartisan support, had representatives from federal and state transportation departments, academia, a private foundation and the transportation, construction and retail industries. It noted that public investment in transportation enabled the nation to become “the world’s primary economic and military superpower,” thanks to “the foresight of private and public sector leaders” who created “the Interstate highway system, the Nation’s freight rail system, and urban mass transit.”

Now America needs “a significant increase in public funding” and “additional private investment,” guided by “a system that ensures each project is designed, approved, and completed quickly,” provides “fully integrated mobility,” “dramatically reduces fatalities and injuries,” “is environmentally sensitive and safe,” “minimizes use of our scarce energy resources,” “erases wasteful delays,” “supports just-in-time delivery,” and “allows economic development and output more significant than ever seen before in history.”

The present transportation system, said the commission, is wasting our “time, money, fuel, clean air, and our competitive edge.”

The commission recommended consolidating 108 federal surface transportation programs into ten: national asset management, enhancing U.S. global competitiveness, congestion relief, safety, access for smaller cities and rural areas, intercity passenger rail, supporting a healthy environment, development of environmentally friendly fuels, public access to federal lands and transportation research.

To pay for the investment, the commission recommended increasing the federal fuel tax and federal truck taxes, a tax on transit trips, fees, tapping customs duties and investment tax credits, plus more investment by the private sector and local and state governments while permitting states to charge tolls on Interstate highways.

The commission was not unanimous. Frank McArdle, senior advisor to the General Contractors Association of New York, had “only one exception” to the recommendations: the nation must move “much more rapidly to the use of centrally-generated power in transportation and non-petroleum fuels.”

Matt Rose, chairman and chief executive officer of the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway, said that expanded rail passenger service on freight railroads must be accompanied by improvements to “ensure that rail freight capacity is not reduced, but enhanced.”

Federal Transportation Secretary Mary Peters voiced several pages of disagreement with the rest of the commission: Its “energy research and investment recommendations are inappropriate”; “Federal Fuel Tax increases are not a solution”; the commission seeks an “unnecessarily large Federal role”; she is opposed to “new Federal restrictions on pricing and private investment”—and more. Her position seems to be that the nation’s present transportation system is good enough, but she appears to be at odds with business leaders.

No national transportation plan is going to please everyone, but this commission has recognized that transportation congestion and oil dependence cannot be cured within the present system and that preserving our place in the world economy requires a new, safe, environmentally friendly and efficient transportation system.

[More “Commuter Crossroads”]

[Return to the home page]

Transfers: A Help and a Hassle

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on Nov. 11, 2007, and is reproduced with permission.

Many commuters who ride public transportation use more than one transit service to get to work. From the passenger’s point of view, transfers are bad: Change transit vehicles and your trip takes longer and often costs more.

Although many Virginia Railway Express, vanpool, carpool and bus commuters can walk to their jobs at the end of their ride, many others have to transfer to Washington Metro trains, local buses or even Maryland Rail Commuter, known by its acronym MARC.

The multitude of transit agencies serving the Washington area can make these transfers confusing. But a Smartrip card ($5 to own one, and then you must add value) will get you all over the metropolitan area, the two major exceptions being the commuter railroads, MARC and VRE. Even they are working to make their ticketing systems compatible with Smartrip cards. You can buy the cards at Metro Center (a hub Metro station in downtown Washington), at Arlington’s Commuter Stores, and at other outlets.

VRE also offers a Transit Link Card that gives you a month of discounted rides on the railroad and unlimited rides on Metrorail.

Scheduling a transfer as part of your commute can be easy or hard, depending on where you want to go. Reaching the Pentagon or Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport is easy: get off VRE at Alexandria or Crystal City and go to the nearby Metro station; a Metro train going your way should arrive within a few minutes.

Bus services mostly connect with Metrorail, which is presumed to run often enough that no matter when your bus arrives, there will be a train soon afterward. Transferring from a train to a bus is another story, because most bus lines run less often than the trains, and you need some planning and maybe a few lessons in the school of hard knocks to figure out a reliable connection.

Planning a new trip using local buses in the Washington area requires research. The metropolitan bus map looks like a bowl of colored spaghetti. Figuring out which buses go where and when can take some time. However, the price is right: you can ride most Metrobus routes for free using a VRE ticket.

Otherwise, the price of transfers is mostly unrelated to their value to passengers. You can ride all the way to Baltimore via MARC for free using a VRE pass (transfer at Union Station). That’s almost a hundred miles from Fredericksburg. Going to College Park, Md., will cost you a lot more even though it’s considerably closer, because you need to ride Metro rather than MARC. Basically you are purchasing individual services from separate agencies and there are few package deals.

In cities where all public transportation is provided by one agency, transfer arrangements tend to be much better. For example, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, serving Boston and its suburbs, has a pass like the Washington area’s Smartrip card, but the system automatically calculates the single best price for your trip. Take a trolley and a bus and you pay only the higher of the two fares, not both.

At the other extreme, a few transit agencies do charge a separate fare for each vehicle you ride, unrelated to the overall distance. Fredericksburg Regional Transit discontinued free transfers earlier this year. Now you pay a new fare for each bus you ride, whether you’re going two miles or ten, but the fare is only a quarter, except for the VRE shuttles, which cost a dollar.

The Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, serving the Philadelphia area, decided this year to discontinue all free transfers and got slapped down in court. School children who ride the rails and public buses to school, along with 45,000 adults, mostly of lower income, would have been affected.

The court took their side because they are dependent on public transportation. A lot of the Washington area’s riders are not, and to keep them on board, we need to make transfers easy and economical.

Integrating all transit ticketing into the Smartrip card system will help. Automatic discounts for transfers and for frequent trips can make public transportation more attractive. Metrorail fares are already based on distance. Joint rail and bus fares based on mileage, with a discount to compensate you for the nuisance of transferring, would put the price more in line with the service.

[More “Commuter Crossroads”]

[Return to the home page]

Commuting Predictions for 2007

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in slightly different form in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on Jan. 7, 2007, and is reproduced with permission.

Virginia is about to solve some of its major transportation problems. Whether you are driving, riding the train, or even walking to work, it turns out that the commuting difficulties you experience all have simple solutions.

Since all of my predictions for 2006 came true (some of you are still sitting at the Falmouth light), you will want to know what the future holds.

First, we can expect some real action from the legislature this year. For decades, the governor, the State Senate and the House of Delegates have been unable to agree as to whether the government should be involved in transportation, and if so, how. Should it be merely an election issue? Should the commonwealth be using tax dollars for roads that are little used during certain hours of the night? Do we really need to spend money on airports when other nearby states have airports that Virginians could use? (Research has shown that many people who use Virginia’s airports do not fly every day or even every week.) Couldn’t the thousands of rail passengers just shift their travel to take advantage of empty roads in the middle of the night? And why should Virginia spend money to expand transportation for the Jamestown 2007 celebration, which might be over before the legislature can even agree on a budget?

This year our elected officials will finally stop their bickering and pass the Responsible Transportation Act. Taxpayers and legislators will rejoice because it takes care of all transportation problems with no new taxes. It says that all citizens are responsible for their own transportation. If you want a longer exit lane from I-95 at Massaponax, then you should get together with everyone else who uses it, buy some land, and build it. You could even buy the Falmouth intersection, which has a constant one-way influx of customers. If you had, say, Dunk a Legislator there you could make a mint.

If you would prefer to invest in railroads, you could buy CSX and run your own trains. Then you would face no more fare increases or service cuts. In fact, rather than spend money on passenger trains, you could ride your own freight trains to work for free.

Speaking of CSX, that leads to my next prediction: CSX will realize that if it’s bad to run trains fast in hot weather, it’s a bad idea in cold weather too. Covering all the bases, CSX will have heat restrictions if the temperature is above 50 degrees Fahrenheit and cold restrictions if the temperature falls below that.

Not all the rail riders’ problems are due to CSX, however, and Virginia Railway Express has a storybook solution to the issue of locomotives breaking down. VRE is organizing Commuters Against Stalled Trains. (We can be identified by the CAST tags on our bags.) When an engine breaks down, we will chant, “I think I can, I think I can.” I have “reviewed the literature,” as we researchers like to say, and this actually seems to have worked.

Finally, I have not forgotten those with the shortest commutes: those who walk to work or school. The Fredericksburg City Council will finally deal with the problem of parked cars obstructing the sidewalks. It will have parking meters installed on the sidewalks.

These “public-private partnerships,” as I refer to them, will put the responsibility for transportation back where it belongs: on the shoulders of those who choose not to stay home.

I also predict that the voters will return all the legislators to Richmond in the fall. How the lawmakers will get there is their own problem.

[More “Commuter Crossroads”]

[Return to the home page]

Busloads of Train Riders

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on March 19, 2006, and is reproduced with permission.

Lots of people are riding intercity buses despite cuts in service over the past few years. But the service is so poor that I think a lot of them would ride trains instead—if trains were available where they want to go. Yet Greyhound could make its service much more palatable to attract and retain bus riders.

The Greyhound service out of Fredericksburg is skimpy: a few trips per day, north and south. That, I learned last month, is because there also is express service between Washington and Richmond, and it skips Fredericksburg.

While a new bus station is being constructed, Greyhound and Fred are operating out of a temporary station across from Carl’s on Princess Anne Street.

With Amtrak service to the Hampton Roads area cut for several weeks because of CSX trackwork, I couldn’t take the train to Williamsburg for a Saturday meeting. I didn’t think I’d be up to driving two or three hours home after the meeting, so I purchased a round-trip bus ticket. Come Saturday morning, a few other passengers were waiting with me for the bus to Richmond, and a few more waiting for a bus going north.

The Richmond bus pulled in right on time. There were a lot of empty seats, but I spotted two other people going to the Williamsburg meeting. Although this was a local bus, from Fredericksburg to Richmond it ran nonstop, and we arrived at the Richmond bus station about an hour later, on time.

This would be an easy way to go to Richmond, except that the bus station, on the Boulevard, is not near much except for the Diamond, where the Richmond Braves play, right across the street.

I and the other travelers going to Williamsburg had computer-generated tickets with dates and bus trip numbers, but here is where Greyhound becomes very unattractive: your ticket is no guarantee that you will get on the bus. An hour before the Norfolk bus was scheduled to leave, people were lining up to make sure they would get on board.

I’d encountered this problem before a few years ago when one of my sons and I got stuck in the downtown Baltimore bus station for hours because the bus filled before we could get on, and we had to get in line for the next one.

This recurring situation has, I’m sure, driven away plenty of passengers. After this trip, I would not take an intercity bus unless I were desperate. Yet the problem could be fixed: Greyhound’s computer could be used to reserve seats on the buses.

Furthermore, the bus was not particularly cheap. Last summer I took Amtrak to Williamsburg and back. The round trip from Fredericksburg was $58. My bus trip last month cost $61. With no guarantee of a seat, who with any reasonable alternative would ride the bus?

With reserved seats (and more comfortable seats) for about the same price, the train would certainly be preferable. My guess is that a lot of those people on the bus I rode would have taken the train if one had been available.

My intercity bus trips during the past few years have convinced me of two things: the people riding the bus now represent a market for better public transportation, and they are a small fraction of the potential passengers for better rail service, because the bus service is so bad that a lot of would-be passengers have stopped riding.

[More “Commuter Crossroads”]

[Return to the home page]

Transportation Funding Is Far Behind

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on March 5, 2006, and is reproduced with permission.

The generations before us invested in the transportation infrastructure we enjoy now, according to Sheila Noll. It’s our turn to create a transportation system for future generations, she said. Noll is president of the Public Transportation Alliance of Hampton Roads; she was addressing the annual meeting of the Virginia Association of Railway Patrons on Feb. 25 in Williamsburg. Although some of her remarks concerned the particulars of transportation in the Hampton Roads area, most of what she said applies as well to the Fredericksburg area and many other parts of Virginia.

At transportation town hall meetings around the Hampton Roads area, Noll said, “citizens spoke loudly and clearly” for more and better public transportation, including buses, light rail and high-speed rail. They are tired of wasted time due to clogged transportation systems, she added.

Besides highways, the area already has local buses, intercity buses, ferries and Amtrak service. Norfolk is planning a light rail line along a disused railroad right of way. Yet all of these do not add up to the capacity needed to provide mobility to residents and visitors, a situation that sounds familiar in Fredericksburg.

Dwight Farmer, a transportation planning engineer, also addressed the meeting. Farmer is executive director of transportation for the Hampton Roads Planning District Commission. Back in 1967, he said, the I-264 corridor connecting Norfolk and Virginia Beach was forecast to eventually carry more than 30,000 vehicles per day, and traffic engineers doubted that it could handle that much. Today, he said, the toll plaza handles over 100,000 vehicles a day. Furthermore, the average number of people in a car has been steadily declining, so that more cars are being used to carry the same number of people. Today, he said, only one car in 10 has two people in it.

The Norfolk light rail line in the same corridor is forecast to carry 30,000 riders per day, and Farmer said that it would have a significant positive impact on travel between the area’s two biggest cities. Noting that transportation forecasts always turn out low, he ominously mentioned another forecast: by 2015, the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel (I-64) will have an average of one major incident per hour all day long. It typically takes an hour to clear the highway after an incident, he said, so the road will be perpetually congested. It’s easy to imagine the same forecast applying to I-95 in even less than nine years.

Despite the problems, Farmer said, it has been a struggle to get funding for any transportation improvements.

Noll pointed out that the Hampton Roads area is the 33rd largest metropolitan area in the country, but it ranks 61st in transportation funding.

That’s a pattern repeated around Virginia as population growth and economic growth outstrip the transportation infrastructure.

We need a long-term transportation funding source adjusted annually for inflation, said Noll.

To put transportation spending in perspective, Farmer pointed out that each of the big auto manufacturers spends more each year on advertising than the entire federal budget for public transportation. He feels that the mentality of public investment is being lost. However, he thinks that local officials—with whom he works daily—agree with the public on the need for more and better transportation.

Noll compared public opinion on transportation to a sleeping giant. We need to increase the number of voices speaking for public transportation, she said. Politicians listen, she emphasized; people need to speak. We must act as a community and each do our part for a viable multimodal transportation system, she said, noting that it’s an issue of funding and priorities.

[More “Commuter Crossroads”]

[Return to the home page]

Predictions About Commuting in 2006

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on Jan. 8, 2006, and is reproduced with permission.

Innovative relief is in sight for the Falmouth intersection, Virginia Railway Express 10-trip ticket holders are about to reap a windfall and a lot more traffic will be moving at 65 miles per hour on Route 3 in the new year. These are my predictions for what we clairvoyants like to call “the foreseeable future.”

Are you tired of sitting in traffic at the Falmouth intersection? That will be a thing of the past (2005). No, traffic is not going to start moving. In fact, the gridlock will be worse than ever. Your car will be going nowhere for hours, but that doesn’t mean you have to just sit there. Shuttle buses will take you downtown to shop and to enjoy events such as the Christmas open house, which will be on Labor Day weekend this year. By the time you return to your car, the light at the Falmouth intersection will be turning green. After moving ahead a few car lengths, you can take a bus back downtown for the Veterans’ Day observance (the Christmas sales will be interrupted for 15 minutes to honor those who died for our freedom). Then it’s back to the Falmouth intersection. By the time you get through the intersection it will be the real Christmas (it falls in December this year), but you’ll have all your shopping done.

Next, there’s good news for those of you who buy VRE 10-trip tickets. No, the price isn’t coming down; it’s not even going to stand still. The good news is that you have latched on to the hot commodity of 2006. Its value is going to soar faster than real estate or gasoline. In fact, my financial advisor told me to scrap my retirement plan, which is based on stock in companies with executives who will shortly be indicted, and put all my money into VRE 10-trip tickets. I will use a few of them to get to work, but I will hold onto the rest until this year’s fare increase. Then I will cash in my tickets and retire.

More good news for VRE riders: I have deciphered the delay announcements. VRE uses an “additive delay” system, in which you are supposed to add up all the announcements, and that will give you the actual length of the delay. For example, on Dec. 22, when I left home, VRE was predicting 15- to 30-minute delays. By the time I got to the station, VRE was predicting 30- to 60-minute delays. 15 + 30 + 30 + 60 = 135 minutes. My train was 134 minutes late. As you can see, the system is remarkably accurate. In 2006, VRE will start sending this information directly to passengers’ pocket calculators.

But what about getting to the station or anywhere else in this area if you have to use Route 3? One of the losing candidates in 2005 proposed building a limited-access highway along Route 3 (this is really true). The candidate was a loser, but the idea was a winner. I predict that the state will put this project on the front burner and do its best to build the new highway by Christmas, which begins in September. To alleviate congestion on Interstate 95, the new road will have really limited access: it will skip the Central Park shopping center and the Spotsylvania Towne Centre, formerly the Spotsylvania Mall. (Isn’t it strange that the park at the center of Fredericksburg is on the extreme edge of the city and that the center of town in Spotsylvania is at the edge of the county?) The Route 3 Bypasse will not even have a junction with I-95; it will go straight to the new downtown parking garage, which unfortunately will fill up by 6 a.m.

Now that you know the shape of things to come (as H. G. Wells put it) for 2006, you probably can’t wait for 2007. I suggest that you head for the Falmouth intersection. By the time you get across it, it will be next year.

[More “Commuter Crossroads”]

[Return to the home page]

Virginia Needs to Plan Transportation Differently

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on Dec. 25, 2005, and is reproduced with permission.

Transportation in Virginia needs to address the needs of all its citizens, giving them transportation choices rather than making driving the standard for everyone and expecting the millions who don’t fit this model to find some workaround. This view of transportation has gone about as far as it can go, and it’s way past time for a new transportation model that addresses the needs of the very young, the very old, the disabled and the poor, not to mention people who would prefer healthful, environmentally friendly alternatives such as walking and bicycling. On Dec. 3, in a transportation town hall meeting at Walker-Grant Middle School, governor-elect Tim Kaine asked for our ideas on the future of transportation in Virginia. Here are some of mine.

First, create statewide transportation systems besides highways and freight railroads. Transportation needs do not end at county and city lines, and neither do the roads. Neither should passenger trains, bicycling routes, or walking trails.

Bike routes and trails and sidewalks have a significant role to play in local travel. The people of Charlottesville know that safe walking and bicycling routes are not just for recreation but are used by adults, children and senior citizens to go places. Under our present system, many people who want to go somewhere are expected to find a ride. What could be a three-mile bicycle ride turns into 12 unnecessary miles of driving as someone makes a round trip to take a passenger somewhere and another round trip to bring the person home. This multiplies congestion and pollution. Safe walking and bicycling routes can alleviate this; however, they require not just paved trails but systems for safety. Every traffic light should have an exclusive pedestrian light as part of its cycle. If no one waiting to cross the street pushes the button, motor traffic is not delayed at all. People who do want to cross the street would get enough time to get across while other traffic stops. Safe walking and biking routes also require incentives. Every developer of every project in Virginia should have to answer a question: What will you do to encourage—not just accommodate—people to travel to and from your development on foot, by bicycle, and by public transportation?

We also are more than ready for a statewide passenger rail system. The Trans-Dominion Express, with four trains a day serving Bristol, Roanoke, Lynchburg, Charlottesville, Washington and Richmond, was partly funded almost six years ago but has yet to leave the station. It would provide transportation choices to millions of Virginians. Fund it fully and make it happen. Something else to begin in 2006—before the Jamestown 2007 celebration—is additional passenger train service to and from Richmond, Newport News, Norfolk and Virginia Beach. The present Amtrak service is infrequent and expensive ($40 or $50 for a round trip from Fredericksburg to Richmond, for example). Four more trains a day on the lines from Richmond to Newport News, Washington and Virginia Beach (which has no passenger trains even though it is the largest city in Virginia) plus the Trans-Dominion Express make 16 trains a day. This is less than Virginia Railway Express runs. It is not going to break the bank, but it is going to make a huge difference in how it is possible to get around our commonwealth.

Second, make the roads safe for safe travelers. Stop licensing drivers who speed, tailgate, run red lights and park on the sidewalk; make those people afraid to drive that way and make the rest of us safe.

Third, make the existing local public transportation systems more than a workaround for people who don’t drive. The Washington Metro is an exception and a model: it is the preferred way for many people to get around the Washington, DC, area. We don’t need rail rapid transit everywhere, but we do need more than infrequent local buses that merely accommodate those who have no other way to get around.

We can afford this. I can afford this. A few years ago I calculated that paying the Fredericksburg gas tax to support VRE was costing me 50 cents a month. Maybe it’s a dollar now. Make it $10 or $20 and give me ways to get around Virginia seven days a week that don’t involve a traffic nightmare. I’ll gladly pay it and I’ll probably get half of it back by not driving so much.

OK, I’ve had my say. How about you? Whether you want to see a different model for transportation in Virginia or are happy with things as they are, you can express your views to the governor, your state delegate, and your state senator at Virginia’s state government website.

[More “Commuter Crossroads”]

[Return to the home page]

Getting Around Two Small Cities: Brattleboro and Fredericksburg

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in slightly different form in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on Oct. 2, 2005, and is reproduced with permission.

|

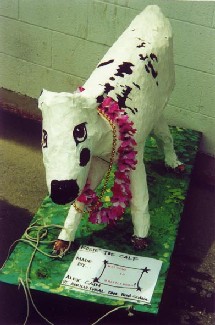

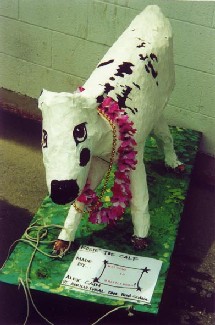

| A passenger and Rosie the Calf outside the Brattleboro station. |

You can walk out of the Econo Lodge and into a shopping center next door, or you can cross the street to an outlet center. And you can walk into town. There are sidewalks the whole way—about a mile. That’s Brattleboro, Vt., a city about the size of Fredericksburg but without the suburbs.

My wife and I arrived by train for our son John’s college graduation from Marlboro College, about 13 miles from Brattleboro. What I found in Brattleboro often reminded me of Fredericksburg and invited comparison of the ways for getting around both cities.

Brattleboro, like Fredericksburg, lies next to a river (the Connecticut), has a central train station, light industries and a community college and has a traditionally laid-out downtown that’s about a mile across. It also has an Interstate Highway and roads leading to other towns and to neighboring New Hampshire.

Compared to Fredericksburg, Brattleboro doesn’t have as many tourist attractions, though it does attract visitors. The scenery is pleasant (there’s a waterfall downtown), and there’s some local history to learn about. The intercity bus station is miles from town, out near an exit from Interstate 5 north of the city. There’s one Amtrak train a day to St. Albans, Vt., with a bus connection to Montreal, and a daily train in the other direction to New York and Washington.

But it’s somewhat easier to get around Brattleboro. There seem to be sidewalks everywhere. Although our hotel was next to an exit on the Interstate, we walked to stores, walked to church, even walked the mile to the train station with one suitcase apiece (it was all downhill). The Walk signs are accompanied by a chirping bird sound, which at first I didn’t connect with the traffic signals. The novelty of a bird sound for crossing the street wore off pretty quickly. Downtown Fredericksburg is not too bad to walk around, but generally we are inviting more traffic and congestion by making many places hard to get to without driving.